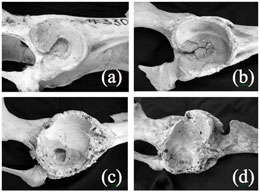

The right hip sockets of moose from Isle Royale, illustrating the progressive bony deterioration associated with osteoarthritis (OA). Panel (a) is a normal hip socket, with an open acetabular fossa (AF), through which a ligament passes through to the head of the femur. Early stages of OA involve the closing of the AF (b). OA eventually develops into severe bone deformations and eventually the complete dislocation of the femur (c, d).

All mammals senesce, that is, experience a decline in body function with increasing age. But we don’t all senesce the same. Some of us are old beyond our years, while others remain youthful as the years roll on. But why? It is a question that has fueled a great deal of research.

Arthritis is a particularly important form of senescence among humans. The causes of arthritis are complex and not well understood. Genetics and joint injury play a role, but don’t tell the whole story. One idea has been that individuals experiencing poor nutrition early in life are more likely to suffer from arthritis later in life. The mechanisms of this idea are not well understood, and evidence to test the idea is also tough to come by.

Recently, the bones of Isle Royale moose have revealed a clue about the causes of arthritis. Each year we conduct necropsies on about 100 different moose. Over the past five decades, we’ve conducted necropsies on more than 4000 different moose.

One of the most basic observations from all these necropsies is that arthritis is common among Isle Royale moose. More than 40% of the moose that survive to at least 10 years of age eventually become arthritic.

Our next observation involved recognizing that some moose die relatively young with arthritis, and others die quite old without it. Why?

The white arrow points to this moose’s metatarsus, which is its rear foot bone. This bull moose was photographed in spring. He has no hair on his shoulders; that was lost to ticks.

When we find the skeletal remains of a moose in the forest, one of the bones that we give a special effort to find is the metatarsus. The metatarsus is a rear foot bone about 13 inches long. On a moose the metatarsus looks like the lower leg of a moose, but that is because moose, like other members of the deer family, walk on the tips of their toes. This bone is especially informative. It stops growing after a moose is about 1 year of age, and experiences about half its growth before a moose is born. Metatarsal length is a permanent record of how much a moose grew as a fetus and during its first year of life. The better nourished a young moose is, the greater the metatarsal length.

We know from measuring the length of a couple thousand metatarsi that nutritional conditions early in life vary tremendously among moose. Some are born in years with much food and easy winters, others are not so fortunate. Some are born to experienced, fit moose; and others are not so fortunate.

The collection of metatarsal bones we collected from necropsies conducted in 2002.

What we learned is that moose with the shortest metatarsi (10th percentile and smaller) had twice the odds of dying with arthritis than the largest (90th percentile and greater) moose.

This link between arthritis and early nutritional health may explain the anthropological observation that arthritis became more prevalent in native Americans as their diet become poorer – the result of relying more on corn and agriculture and less on hunting and gathering, especially after Spanish missions began to concentrate native Americans and encourage agriculture. These patterns are also consistent with emerging knowledge, which suggests senescence in older humans is affected by nutrition they experience as young people.

And, we learned more. Nutritional conditions early in life are often similar for an entire cohort of moose. A cohort of moose are all the moose born in the same year. As a result, an entire cohort of moose may have a similar predisposition to developing arthritis later in life. For example, the moose born between 1969 and 1971 experienced severe winters and much competition for food. Eighty percent of these moose developed arthritis as they reached old age, a decade later. Conversely, only 20% of the moose born between 1949 and 1952 ever developed arthritis. These moose were born when winters were mild and moose density was low.

Wolves are selective predators and rely on moose that are weakened in some way. What we learned is that environmental conditions today affect the prevalence of arthritic moose a decade later, which can affect wolf predation. Long time lags such as this are one of the key reasons why ecological systems are complex and difficult to predict. Arthritis is not merely a physiological phenomena, it can also be an ecological phenomena.