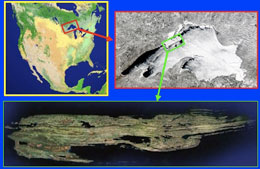

Isle Royale is a remote wilderness island, in one of the planet’s most unforgiving lakes, Lake Superior, North America. Isle Royale was born of fire and smoke, from lava that poured from a crack in the earth’s crust a billion years ago. She was shaped of ice and water, from glaciers that piled rich sediments in the south and scoured her bare in the north. Today, she is a corrugated series of ridges and valley that follow her long axis. She is mostly green with boreal forest, speckled with blue inland lakes, and rimmed in the dark grey basaltic rocks that separate her from Lake Superior.

Isle Royale has always been isolated. On an easy day, she is separated from the rest of the world by 24 km of icy waters. On many days, she is further protected by fog, ice, wind, waves and storms. Offshore, just beneath the surface, she is littered with the skeletons of no fewer than a dozen ships.

Even our mammalian brethren have found getting to Isle Royale difficult. Of the 50 or so mammal species that live on the mainland, only about 20 mammal species call Isle Royale home. And several that once called it home have since gone extinct – caribou, coyote, sharp-tailed grouse.

Humans have never regularly lived year-round on Isle Royale. For at least three thousand years, Native Americans used Isle Royale for copper and fish, but mostly limited their visits to the summer. Nineteenth century Americans did the same. Today, Isle Royale is used for wilderness recreation, but only in the summer. We have only been fair-weather visitors.

Biogeography is the term scientists use to speak about how it is that the ecology of a place is so very much influenced by the geography of a place. Isle Royale’s biogeography is well suited for the goals of the wolf-moose project. A primary goal is to understand how and why the wolf and moose populations on Isle Royale fluctuate over the years.

If by some accident of the Earth’s geologic history

Isle Royale had been smaller than it is,

it would be too small to support a wolf population;

Isle Royale had been larger than it is,

it would be too large to effectively study the moose population;

Isle Royale had been further from the mainland than it is,

wolves and moose may never have made it to Isle Royale;

Isle Royale were closer to the mainland than it is,

other species now absence on Isle Royale would be interacting with wolves and moose,

obscuring our ability to focus on just wolves and moose.

Isle Royale is not too close, not too far, not too small, and not too large.

Nature is difficult to understand because it usually includes interactions among so many species. Isle Royale is different. Here, wolves are the only predator of moose, and moose are essentially the only food for wolves. It’s very important that some of our observations of nature include places where the relationships are relatively simple. That simplicity is key to understanding more complex places. And if we cannot understand the simple places, it says something about our ability to understand more complex places.

To understand nature it also helps to observe an ecosystem where human impact is limited. On Isle Royale, people do not hunt wolves or moose or cut the forest. It is a very rare place on the planet where wolves, their prey, and the plants that support the prey are all left unharvested by humans. Isle Royale is remarkable, because nature runs wild there.

Because the wolves and moose on Isle Royale are isolated, they are unable to leave. The population fluctuations we observe are not the mere wanderings of wolves and moose to or from the island. Instead, wolf fluctuations result from the birth of pups when they can be supported by the flesh of moose, and wolf deaths that occur when food is scarce. Moose fluctuations result from the birth of calves and survival of adult moose, both of which depend on climate, forest growth, ticks, and wolf predation.